IN 2010, HENRY EVANSsaw a robot on TV. It was a PR2, from the robotics company Willow Garage, and Georgia Tech robotics professor Charlie Kemp was demonstrating how the PR2 was able to locate a person and bring them a bottle of medicine. For most of the people watching that day, the PR2 was little more than a novelty. But for Evans, the robot had the potential to be life changing. “I imagined PR2 as my body surrogate,” Evans says. “I imagined using it as a way to once again manipulate my physical environment after years of just lying in bed.”

Eight years earlier, at the age of 40, Henry was working as a CFO in Silicon Valley when he suffered a strokelike attack caused by a birth defect, and overnight, became a nonspeaking person with quadriplegia. “One day I was a 6’4”, 200 Lb. executive,” Evans wrote on his blog in 2006. “I had always been fiercely independent, probably to a fault. With one stroke I became completely dependent for everything…. Every single thing I want done, I have to ask someone else to do, and depend on them to do it.” Evans is able to move his eyes, head, and neck, and slightly move his left thumb. He can control a computer cursor using head movements and an onscreen keyboard to type at about 15 words per minute, which is how he communicated with IEEE Spectrum for this story.

Henry Evans shaves with the assistance of a PR2 robot in 2012.

After getting in contact with Kemp at Georgia Tech, and in partnership with Willow Garage, Evans and his wife Jane began collaborating with the roboticists on a project called Robots for Humanity. The goal was to find ways of extending independence for people with disabilities, helping them and, just as importantly, their caregivers live better and more fulfilling lives. The PR2 was the first of many assistive technologies developed through Robots for Humanity, and Henry was eventually able to use the robot to (among other things) help himself shave and scratch his own itch for the first time in a decade.

“Robots are something that was always science fiction for me,” Jane Evans told me. “When I first began this journey with Henry, it never entered my mind that I’d have a robot in my house. But I told Henry, ‘I’m ready to take this adventure with you.’ Everybody needs a purpose in life. Henry lost that purpose when he became trapped in his body, and to see him embrace a new purpose—that gave my husband his life back.”

Henry stresses that an assistive device must not only increase the independence of the disabled person but also make the caregiver’s life easier. “Caregivers are super busy and have no interest in (and often no aptitude for) technology,” he explains. “So if it isn’t dead simple to set up and it doesn’t save them a meaningful amount of time, it very simply won’t get used.”

While the PR2 had a lot of potential, it was too big, too expensive, and too technical for regular real-world use. “It cost $400,000,” Jane recalls. “It weighed 400 pounds. It could destroy our house if it ran into things! But I realized that the PR2 is like the first computers—and if this is what it takes to learn how to help somebody, it’s worth it.”

For Henry and Jane, the PR2 was a research project rather than a helpful tool. It was the same for Kemp at Georgia Tech—a robot as impractical as the PR2 could never have a direct impact outside of a research context. And Kemp had bigger ambitions. “Right from the beginning, we were trying to take our robots out to real homes and interact with real people,” he says. To do that with a PR2 required the assistance of a team of experienced roboticists and a truck with a powered lift gate. Eight years into the Robots for Humanity project, they still didn’t have a robot that was practical enough for people like Henry and Jane to actually use. “I found that incredibly frustrating,” Kemp recalls.

In 2016, Kemp started working on the design of a new robot. The robot would leverage years of advances in hardware and computing power to do many of the things that the PR2 could do, but in a way that was simple, safe, and affordable. Kemp found a kindred spirit in Aaron Edsinger, who like Kemp had earned a Ph.D. at MIT under Rodney Brooks. Edsinger then cofounded a robotics startup that was acquired by Google in 2013. “I’d become frustrated with the complexity of the robots being built to do manipulation in home environments and around people,” says Edsinger. “[Kemp’s idea] solved a lot of problems in an elegant way.” In 2017, Kemp and Edsinger founded Hello Robot to make their vision real.

The robot that Kemp and Edsinger designed is called Stretch. It’s small and lightweight, easily movable by one person. And with a commercial price of US $20,000, Stretch is a tiny fraction of the cost of a PR2. The lower cost is due to Stretch’s simplicity—it has a single arm, with just enough degrees of freedom to allow it to move up and down and extend and retract, along with a wrist joint that bends back and forth. The gripper on the end of the arm is based on a popular (and inexpensive) assistive grasping tool that Kemp found on Amazon. Sensing is focused on functional requirements, with basic obstacle avoidance for the base along with a depth camera on a pan-and-tilt head at the top of the robot. Stretch is also capable of performing basic tasks autonomously, like grasping objects and moving from room to room.

This minimalist approach to mobile manipulation has benefits beyond keeping Stretch affordable. Robots can be difficult to manually control, and each additional joint adds extra complexity. Even for non-disabled users, directing a robot with many different degrees of freedom using a keyboard or a game pad can be tedious, and requires substantial experience to do well. Stretch’s simplicity can make it a more practical tool than robots with more sensors or degrees of freedom, especially for novice users, or for users with impairments that may limit how they’re able to interact with the robot.

A Stretch robot under Henry Evans’s control helps his wife, Jane, with meal prep and cleanup.

“The most important thing for Stretch to be doing for a patient is to give meaning to their life,” explains Jane Evans. “That translates into contributing to certain activities that make the house run, so that they don’t feel worthless. Stretch can relieve some of the caregiver burden so that the caregiver can spend more time with the patient.” Henry is acutely aware of this burden, which is why his focus with Stretch is on “mundane, repetitive tasks that otherwise take caregiver time.”

Vy Nguyen is an occupational therapist who has been working with Hello Robot to integrate Stretch into a caregiving role. With a $2.5 million Small Business Innovation Research grant from the National Institutes of Health and in partnership with Wendy Rogers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Maya Cakmak at the University of Washington, Nguyen is helping to find ways that Stretch can be useful in the Evans’s daily lives.

There are many tasks that can be frustrating for the patient to depend on the caregiver for, says Nguyen. Several times an hour, Henry suffers from itches that he cannot scratch, and which he describes as debilitating. Rather than having to ask Jane for help, Henry can instead have Stretch pick up a scratching tool and use the robot to scratch those itches himself. While this may seem like a relatively small thing, it’s hugely meaningful for Henry, improving his quality of life while reducing his reliance on family and caregivers. “Stretch can bridge the gap between the things that Henry did before his stroke and the things he aspires to do now by enabling him to accomplish his everyday activities and personal goals in a different and adaptable way via a robot,” Nguyen explains. “Stretch becomes an extension of Henry himself.”

This is a unique property of a mobile robot that makes it especially valuable for people with disabilities: Stretch gives Henry his own agency in the world, which opens up possibilities that go far beyond traditional occupational therapy. “The researchers are very creative and have found several uses for Stretch that I never would have imagined,” Henry notes. Through Stretch, Henry has been able to play poker with his friends without having to rely on a teammate to handle his cards. He can send recipes to a printer, retrieve them, and bring them to Jane in the kitchen as she cooks. He can help Jane deliver meals, clear dishes away for her, and even transport a basket of laundry to the laundry room. Simple tasks like these are perhaps the most meaningful, Jane says. “How do you make that person feel like what they’re contributing is important and worthwhile? I saw Stretch being able to tap into that. That’s huge.”

One day, Henry used Stretch to give Jane a rose. Before that, she says, “Every time he would pick flowers for me, I’m thanking Henry along with the caregiver. But when Henry handed me the rose through Stretch, there was no one else to thank but him. And the joy in his face when he handed me that rose was unbelievable.”

Henry has also been able to use Stretch to interact with his three-year-old granddaughter, who isn’t quite old enough to understand his disability and previously saw him, says Jane, as something like a piece of furniture. Through Stretch, Henry has been able to play little games of basketball and bowling with his granddaughter, who calls him “Papa Wheelie.” “She knows it’s Henry,” says Nguyen, “and the robot helped her see him as a person who can play with and have fun with her in a very cool way.”

The person working the hardest to transform Stretch into a practical tool is Henry. That means “pushing the robot to its limits to see all it can do,” he says. While Stretch is physically capable of doing many things (and Henry has extended those capabilities by designing custom accessories for the robot), one of the biggest challenges for the user is finding the right way to tell the robot exactly how to do what you want it to do.

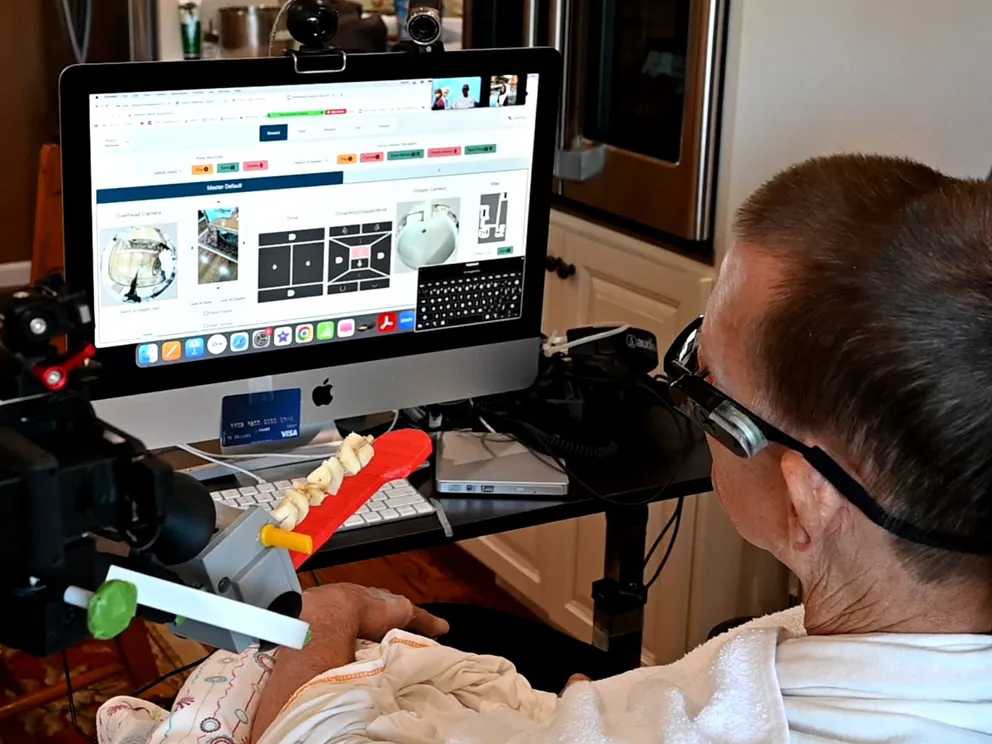

Henry collaborated with the researchers to develop his own graphical user interface to make manual control of Stretch easier, with multiple camera views and large onscreen buttons. But Stretch’s potential for partially or fully autonomous operation is ultimately what will make the robot most successful. The robot relies on “a very particular kind of autonomy, called assistive autonomy,” Jane explains. “That is, Henry is in control of the robot, but the robot is making it easier for Henry to do what he wants to do.” Picking up his scratching tool, for example, is tedious and time consuming under manual control, because the robot has to be moved into exactly the right position to grasp the tool. Assistive autonomy gives Henry higher-level control, so that he can direct Stretch to move into the right position on its own. Stretch now has a menu of prerecorded movement subroutines that Henry can choose from. “I can train the robot to perform a series of movements quickly, but I’m still in complete control of what those movements are,” he says.

Henry adds that getting the robot’s assistive autonomy to a point where it’s functional and easy to use is the biggest challenge right now. Stretch can autonomously navigate through the house, and the arm and gripper can be controlled reliably as well. But more work needs to be done on providing simple interfaces (like voice control), and on making sure that the robot is easy to turn on and doesn’t shut itself off unexpectedly. It is, after all, still research hardware. Once the challenges with autonomy, interfaces, and reliability are addressed, Henry says, “the conversation will turn to cost issues.”

Henry Evans uses a Stretch robot to feed himself scrambled eggs.

A $20,000 price tag for a robot is substantial, and the question is whether Stretch can become useful enough to justify its cost for people with cognitive and physical impairments. “We’re going to keep iterating to make Stretch more affordable,” says Hello Robot’s Charlie Kemp. “We want to make robots for the home that can be used by everyone, and we know that affordability is a requirement for most homes.”

But even at its current price, if Stretch is able to reduce the need for a human caregiver in some situations, the robot will start to pay for itself. Human care is very expensive—the nationwide average is over $5,000 per month for a home health aide, which is simply unaffordable for many people, and a robot that could reduce the need for human care by a few hours a week would pay for itself within just a few years. And this isn’t taking into account the value of care given by relatives. Even for the Evanses, who do have a hired caregiver, much of Henry’s daily care falls to Jane. This is a common situation for families to find themselves in, and it’s also where Stretch can be especially helpful: by allowing people like Henry to manage more of their own needs without having to rely exclusively on someone else’s help.

Henry Evans uses his custom graphical user interface to control the Stretch robot to pick up a towel,

place the towel in a laundry basket, and then tow the laundry basket to the laundry room.

Stretch does still have some significant limitations. The robot can lift only about 2 kilograms, so it can’t manipulate Henry’s body or limbs, for example. It also has no way of going up and down stairs, is not designed to go outside, and still requires a lot of technical intervention. And no matter how capable Stretch (or robots like Stretch) become, Jane Evans is sure they will never be able to replace human caregivers, nor would she want them to. “It’s the look in the eye from one person to another,” she says. “It’s the words that come out of you, the emotions. The human touch is so important. That understanding, that compassion—a robot cannot replace that.”

Stretch may still be a long way from becoming a consumer product, but there’s certainly interest in it, says Nguyen. “I’ve spoken with other people who have paralysis, and they would like a Stretch to promote their independence and reduce the amount of assistance they frequently ask their caregivers to provide.” Perhaps we should judge an assistive robot’s usefulness not by the tasks it can perform for a patient, but rather on what the robot represents for that patient, and for their family and caregivers. Henry and Jane’s experience shows that even a robot with limited capabilities can have an enormous impact on the user. As robots get more capable, that impact will only increase.

“I definitely see robots like Stretch being in people’s homes,” says Jane. “When, is the question? I don’t feel like it’s eons away. I think we are getting close.” Helpful home robots can’t come soon enough, as Jane reminds us: “We are all going to be there one day, in some way, shape, or form.” Human society is aging rapidly. Most of us will eventually need some assistance with activities of daily living, and before then, we’ll be assisting our friends and family. Robots have the potential to ease that burden for everyone.

And for Henry Evans, Stretch is already making a difference. “They say the last thing to die is hope,” Henry says. “For the severely disabled, for whom miraculous medical breakthroughs don’t seem feasible in our lifetimes, robots are the best hope for significant independence.”

The article is reproduced on the website:https://spectrum.ieee.org/stretch-assistive-robot

Please click on the link below to read more:

Robots: The Bridge Connecting AI with the Physical World

Reeman Robotics and the Future of Cybersecurity: A Response to the ICC Cyberattack

Would you like to know more about robots:https://deliveryrobotic.com/

robotics、reeman 、ai、delivery robot、autonomous delivery robot 、factory、handling、handling robot、agv robot、robot chassis、mobile robot、autonomous mobile robot、mobile robot chassis、agv、AMR 、AMR robot、logistics robot、handling robot、agv chassis、package delivery robot、factory delivery robots, workshop material delivery robots、transport robot、porter robot、grocery delivery robot、cartken robot、parts delivery robot、warehouse robots、unmanned delivery、document delivery robot、courier delivery robot、office delivery robot、Food processing plant、digital factory 、garment factory